| #5 | The Brutalist & Zdzisław Beksiński’s paintings

Plus: The Caretaker’s music & Henri Prestes photographs

The Brutalist — Corbet’s fresco of a disfigured American Dream

Just when The Brutalist started hitting the festivals, Anne Thompson and Ryan Lattanzio, on their IndieWire ScreenTalk podcast, weren’t sure if the new Brady Corbet movie was a lengthy 215-minute epic that was closer to a Tár or a, say, The Master. Ryan heard that it was closer to The Master, as the two films’ core study power dynamics within a male relationship, but drawing a parallel with Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood would also have been a fair comparison. They both act as gigantic frescos in their desire to cover a large chunk of the life of their protagonist in the subgenre of “fictional character biopic”, both dealing with a certain form of disfigured American Dream. In the first third of The Brutalist, Adrien Brody’s character László even mentions a couple of times that, besides shovelling coal in a shipyard, he’s also designing a bowling alley — an oddly specific assignment that makes you wonder if Corbet didn’t wink at Paul Thomas Anderson here, implying that László could’ve built these extravagant private lanes where Daniel Plainview and Eli Sunday finally come to terms.

But László and Plainview share more than laminated floors and pins, the pair starting from the absolute bottom before crawling their way up the ladder. A survivor from Buchenwald, László joins his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola) in Philadelphia to work in his humble furniture shop, snarling at how assimilated his cousin became, a Catholic wife by his side and his maternal accent hidden deep in his pocket. The two manage to work for a daddy’s boy who wants to renovate a library in their mansion — a side business where László shows just how avant-garde and brilliant his architect mind is, getting the attention of the daddy in question, Harrison (Guy Pearce), a successful businessman eager to shine by proxy. The film dives into this intricate transactional relationship and gains momentum through a sequence of remarkable scenes, sometimes as simple as an aerial shot of a train derailing, its carefully cut sheets of concrete breaking in their fall, underlined by Blumberg’s oppressive score. The second part, after the 15-minute intermission, opens with László’s wife's delayed arrival in the U.S. where she is terrified by her husband’s reaction as she concealed her disease that now forces her to be in a wheelchair. Another memorable — and key — scene follows László and Harrison in a marble quarry in Italy, where a surreal party happens in labyrinthian caverns.

László nourishes his addictions here, drinking more than a liver can take and capping the evening with heroin in an isolated tunnel. A drunk Harrison joins him and encourages him to throw up and to “let it all out”, before forcing himself on his protege in a glacial single-shot scene. Many raised their voices regarding this scene that felt unmotivated and out of left field, including and in their brilliant reviews that are worth a read, but I believe this act can be traced back to one of Pearce’s character's rare confessions at a dinner, where his facade crumbles for a brief instant as he admits being himself no great architect or no great writer, simply a man who did good for himself through means that, in this moment, do not seem quite to his liking. And when Pearce starts to assault the man whose talents he wishes he had, he asks him “Who do you think you are?”, the lyrics from Italian singer Mina still echoing in the tunnel from the nearby party: “You are my destiny / You share my reverie / You’re more than life to me / That’s what you are…” Harrison’s morbid rape acts as an attempt to confirm his superiority over his protege and to reassure his staggeringly low self-esteem that, if he can sodomize who he thinks is more brilliant than him, it means he still owns him. When this secret is revealed to his own family later on (including his son, his most fervent defender, who himself possibly forced himself on László’s mute niece), Pearce’s character vanishes, leading to a magnificent search scene to close his arc and put an end to a loud and monstrous character in a shameful silence.

Besides a solid performance that should make him a frontrunner for Best Supporting Actor, Guy Pearce’s character was written with nuances and through increments that allowed him to naturally flow within the bigger narrative, but other gravitational sub-themes and storylines struggled to do so with the same ease. It is natural for a fresco to take detours and wander in, at times, slightly more circumstantial topics, but Corbet and his life partner and co-writer Mona Fastvold seem to have an appetite so big in their urge to cover so much ground that they spread the narrative thin and lost a certain form of cohesion. The film can feel disjointed, especially in its second half, as many have mentioned, and echoes its score that, at times, seems to search for its own melody.

The Brutalist closes in 1980 in Venice, where László is the subject of a retrospective, including the colossal Van Buren Centre that Harrison commissioned him to build decades ago. It is explicitly revealed that László designed it to echo the concentration camps — naked and small rooms with tall ceilings and hidden corridors to connect the different sections, highlighting how he still felt connected to his wife who was in Dachau — as a way to process trauma. This notion was kept elusive throughout the narrative, and even though it can be charming to think retrospectively on it, this primary knot of how an artist represents himself through creation — a language breaking barriers and revealing what words can’t, especially considering László tendency to mutism — could’ve been weaved through the entire runtime for a stronger thematic resonance.

This final scene in Italy also echoes one of the first real conversations between László and Harrison, where László explains his rapport with architecture and states: “My buildings were designed to endure such erosion.” It is a reference to brutalism architecture itself, but also a hint that his buildings will continue to carry parts of him after his physical body collapses, just like his pre-war buildings in Budapest survived the bombs. László built an extension of himself and became, somehow, immortal—his secrets, trauma, and exhaustive story in each square inch of the raw concrete. He listens to his niece giving this speech, himself sitting in a wheelchair now, cadaveric and miserable, having hidden his entire self in cement. It is precisely that self that the audience might be left wanting more in Corbet’s fresco that nonetheless feels like one of those rare behemoths, the ones that took everything from their creators to put together on a small budget, the ones that tested resilience and stamina, the ones bigger than life that leave a mark and that we’re fortunate to watch.

Reviews mentioned:

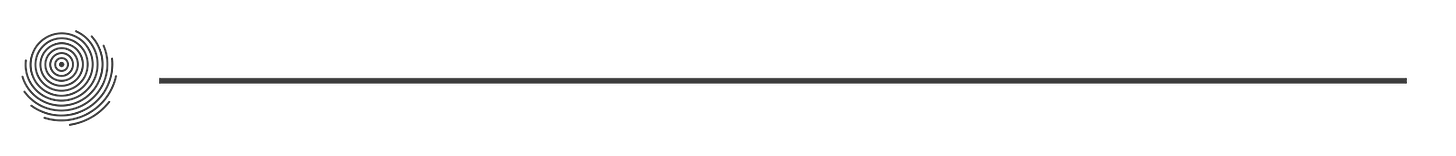

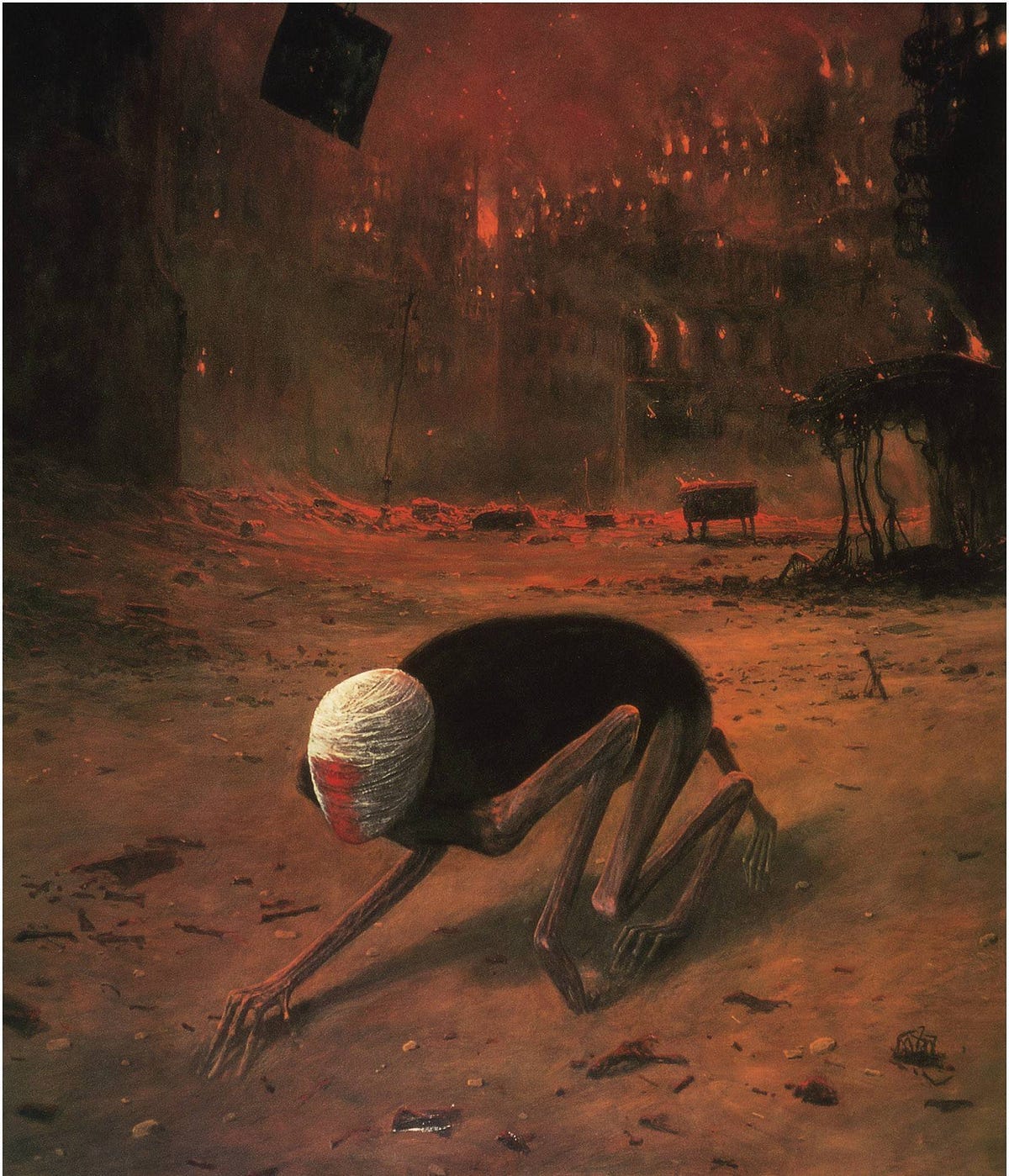

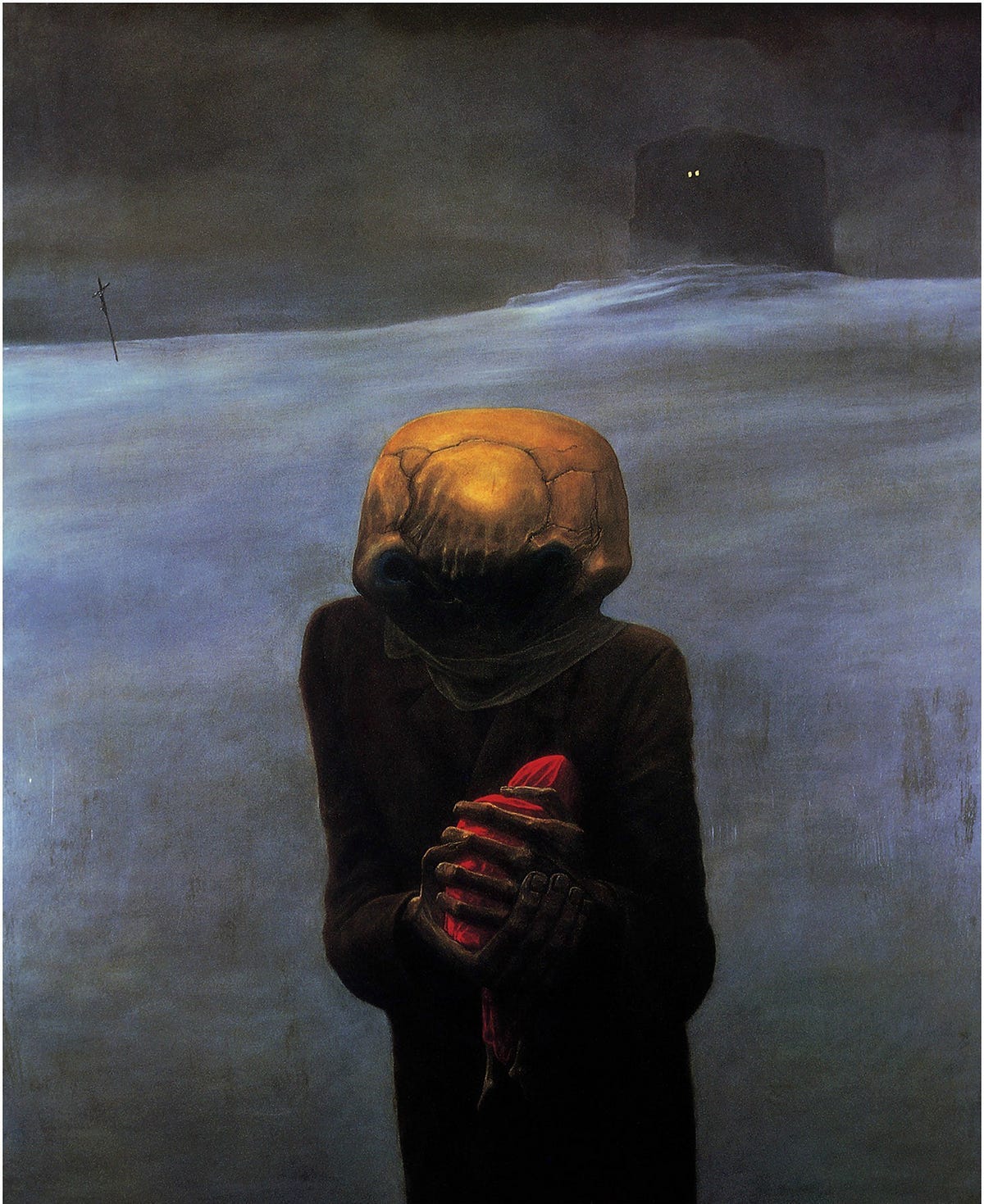

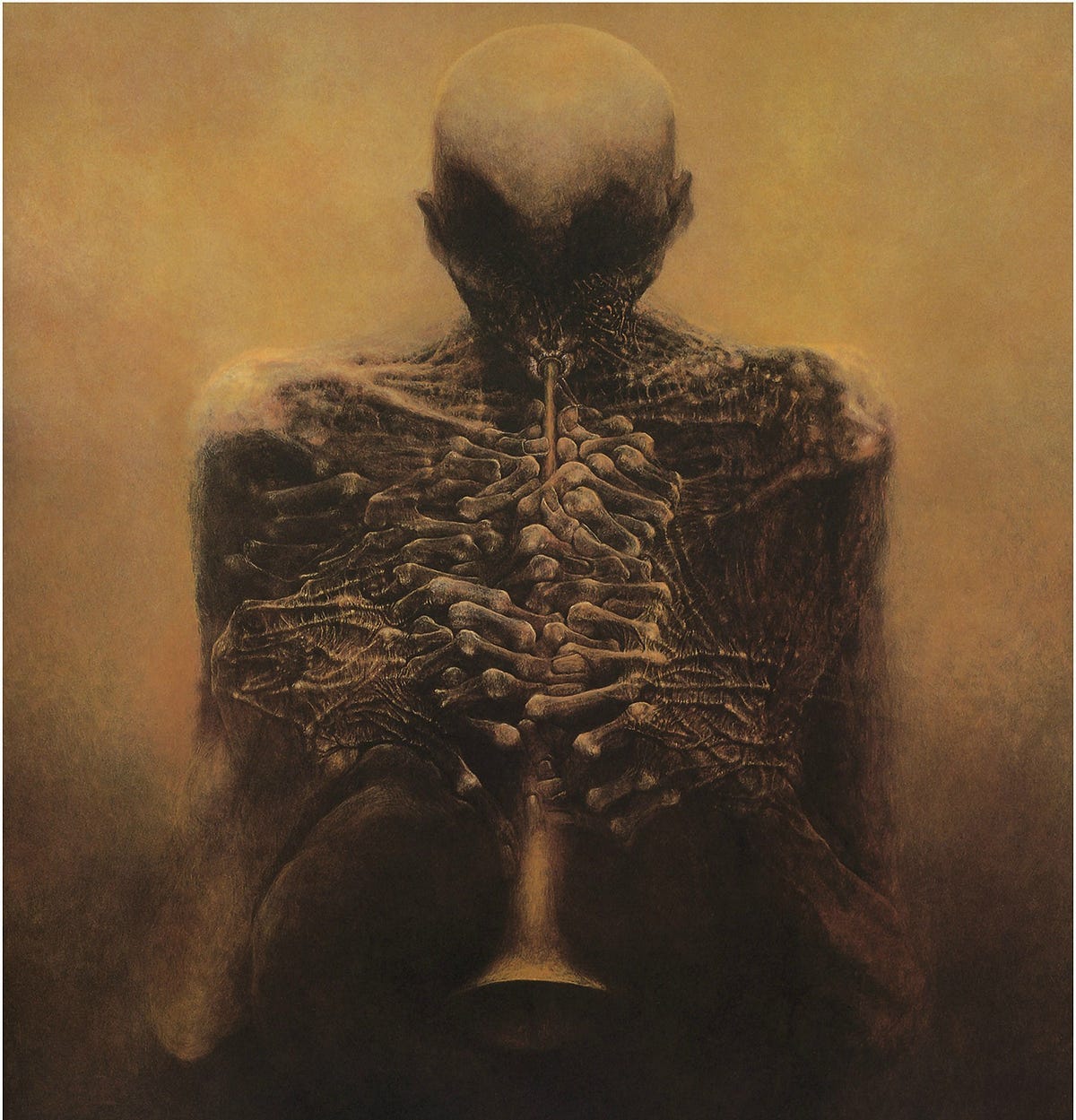

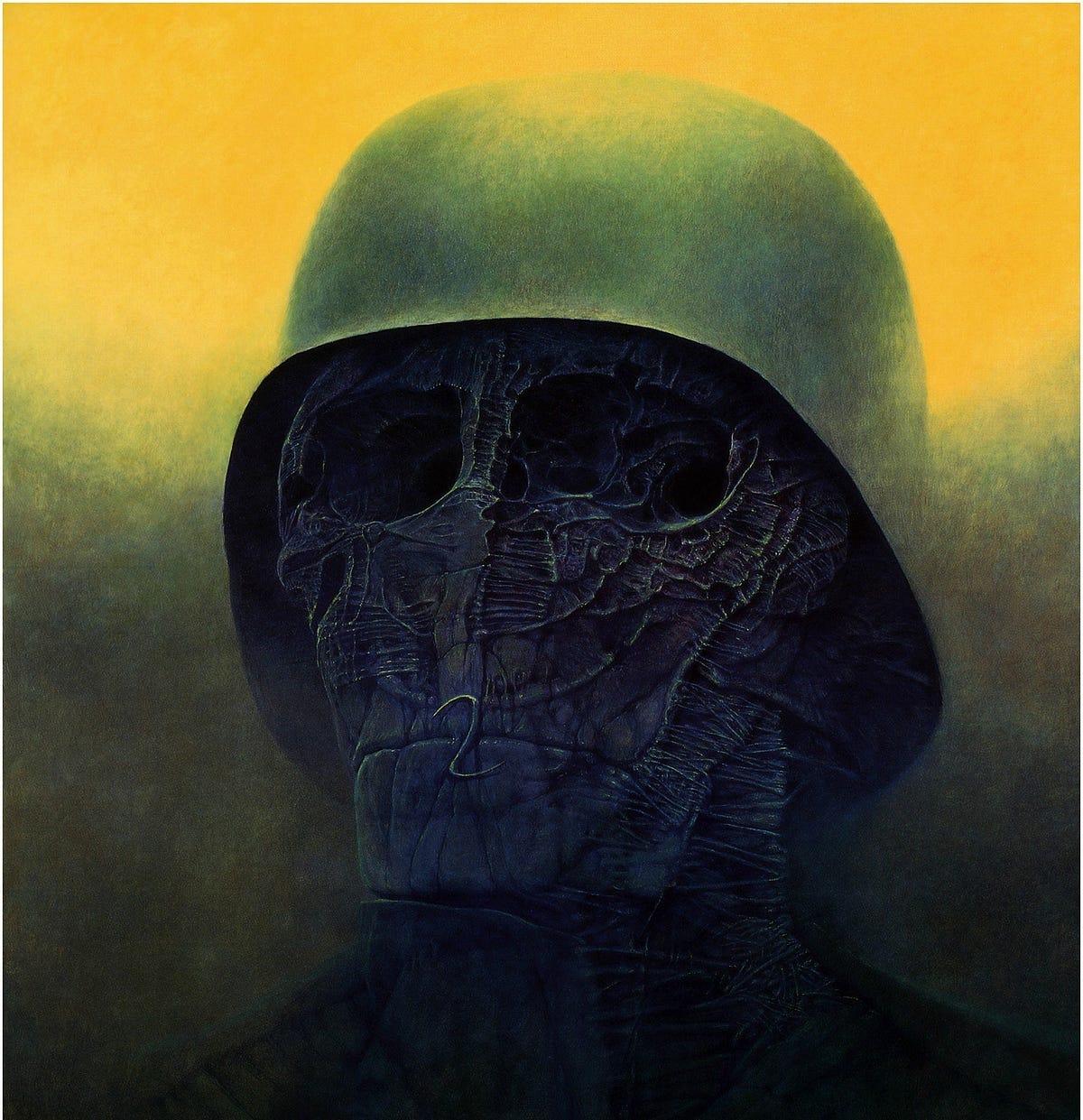

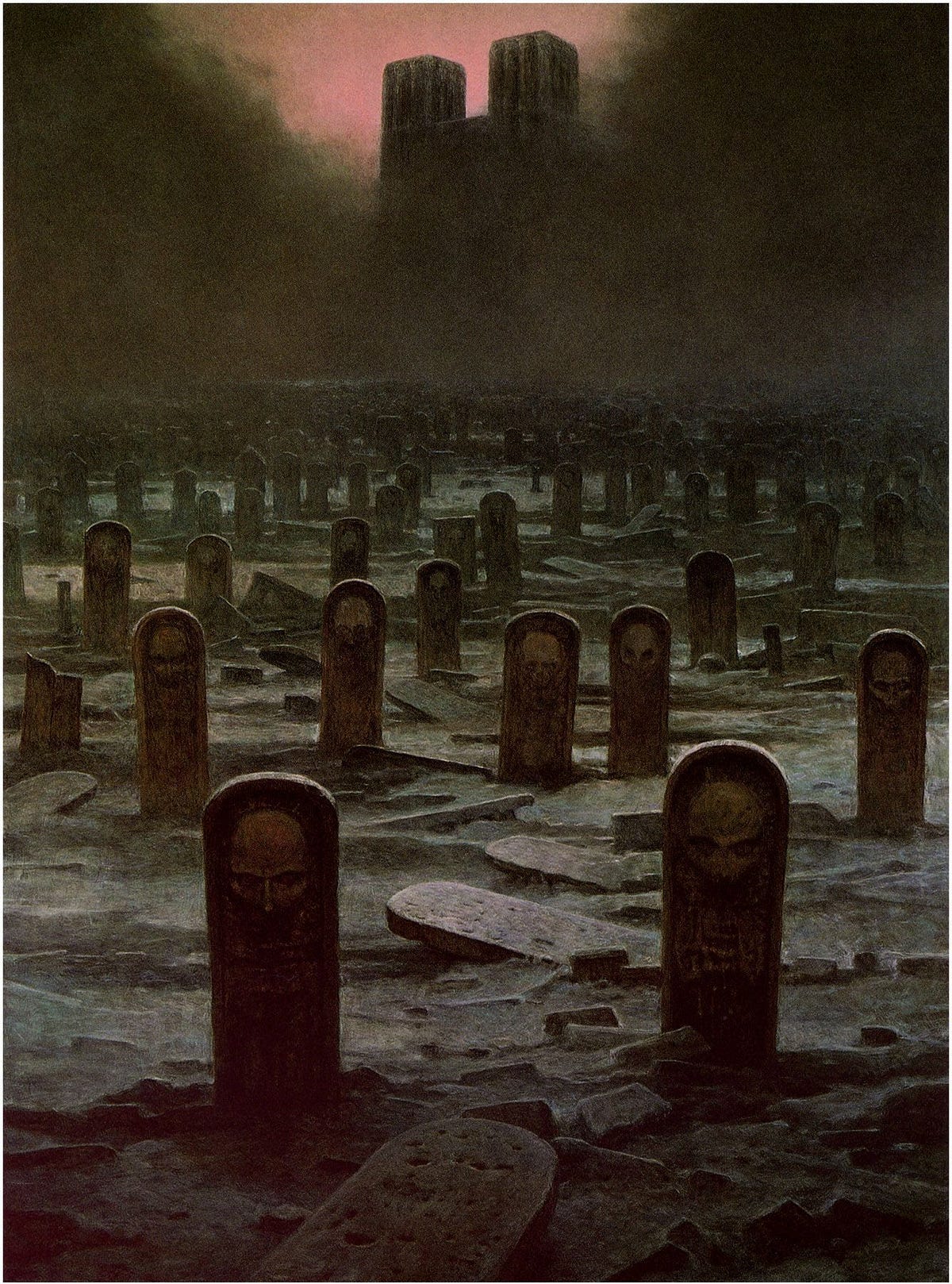

The nightmares of Zdzisław Beksiński

A squall shakes a giant tree tilting on the left, its naked branches about to crack. Some of them are not branches but bones—knees and elbows intertwined and bent in a chaotic cobweb. The air is acidic, full of mustard gas cloaking everything in a thick orange fog. Each branch is a corpse, each branch is a sack of bones shrieking its ache.

Nature is rare in Zdzisław Beksiński’s paintings, but when present it still evokes death and decay, two red lines in the Polish artist’s work. From the late '60s to the mid-80s, he produced his most renowned paintings, with an instantly recognizable style that he used to depict macabre scenes of what’s left after war and life itself.

A child while World War II was raging in Poland, Beksiński painted his dreams and memories where dismal and gigantic figures crawl on burnt and dry lands, no flesh between their skin and carcass. Anemic creatures and children wander amongst graves and vestiges from the past while gigantic corpses play the trumpet with countless bony fingers or seem to stare at the past even though it’s just empty cavities where their eyes should be. Each painting acts as a bleak fable in a world that ceased to be.

Some scenes seem so rich and specific that it is challenging not to attach a narrative behind them, yet Zdzisław Beksiński was reluctant to find meaning behind his work, sometimes even mocking those who did. He never named his pieces and rarely talked about them, simply stating that his work was misunderstood and was, in fact, quite humorous and optimistic. But he was known to be extremely methodical and demanding in his practice, spending hours perfecting details on the canvas, and did destroy a portion of his works in 1977—two elements that would suggest that there is a deep personal connection and even secrets on the canvas. His tendency to privacy and natural bashfulness might have gotten in the way of him talking about his paintings, and so we’re left wandering in his substantial catalog of artworks, unguided, unaided, witnesses to one of the bleakest minds out there.

Find more on this authorized Instagram account.

The Caretaker’s waltz in forsaken ballrooms

“You can’t trust any memories at all, can you? Because it’s all glitched. It’s all nonsense in a way.”

— Ivan Seal, illustrator and collaborator of The Caretaker, during an interview for The Quietus

In December 2010, James Leyland Kirby found a collection of old pre-World War II 78 rpm ballroom records in Brooklyn, paid ten dollars for it, and started playing them in Berlin sometime later. He transferred them on a digital recorder and manipulated them, adding textures, slowing them down, looping them left and right. This marked the start of an album he never anticipated and would come out in June 2011: An Empty Bliss Beyond This World.

Kirby already worked with ballroom records at this stage in his career, but this release marked a turn in his gigantic “The Caretaker” project where he evokes the gradual deterioration of memory in a nostalgic and melancholy-bathed tone.

“Famously, people as they get older have started seeing dead people, people from the past, and that’s their reality because the brain’s misfiring. I’m very interested in these kinds of stories. Music’s probably the last thing to go for a lot of people with advanced Alzheimer’s.”

— Leyland Kirby on an interview with The Quietus

These ballroom songs occupy a space in our collective memories, associated with moments of delicate pleasures, romances, light and frivolous spirits. Kirby invites ghosts into this lighthearted waltz, and opens the door for a layer of melancholia, decay, and even death, creating this stunning dichotomy in the listeners who find themselves ambling into echoey rooms that become a somber yet soothing lair among the cadavers of the past.

He went on to work on the most substantial project of his career: six connected records under the umbrella “Everywhere at the End of Time”, this time focusing on the stages of dementia through a carefully crafted narrative. The first three stages are somewhat evocative of his earlier work on An Empty Bliss Beyond This World, transpiring nostalgia and a somewhat pleasant melancholy, life remembered through a foggy veil, but the last three stages mark something new for Kirby who created a dark yet audible chaos. These records are both the hardest to listen to and the ones that have the most weight and substance, mirroring Kirby’s interpretation of the sheer confusion and panic associated with the disease. The final stage leads us toward a moment of terminal lucidity where a sublime choir resonates one last time, followed by a minute of silence where, at last, we are no more.

Kirby’s work isn’t as much about music composition itself but how he affects our collective memories through his specific transformation of existing material. This hauntology approach is a fertile ground for reflection on our own memory and relationship to the past, and acts as a form of death meditation. Eric Schwitzgebel, in his essay “The penumbral plunge” remarked that, at its best, art is a form of philosophy, and The Caretaker managed to be exactly that.

[…] At its best and most ambitious, art transcends decoration and amusement, confronting us with, exploring and playing with the puzzles of human existence. In their most awesome manifestations, the human arts and sciences merge into philosophy. They express and develop our philosophical impulses.

Henri Prestes and the vestiges of memory

Your alarm clock goes off and you open your eyes, the remnants of a dream still vividly imprinted in your brain—you can feel it, smell it, sense it in your bones, it’s all that exists in this ethereal moment of half-consciousness. You rub your eyes and your hair, sip water, and the vividness is gone, now nothing but a streak of smoke, like a distant memory from your childhood.

This is what Henri Prestes’ photographs feel like, their slightly surreal and foggy nature echoing an imprecise memory, closer to a feeling than a clear cognitive recollection of events.

In his series “Outer Edges”, Prestes captures humble buildings in a cold mid-winter, evoking a sense of utter desolation and creating a bleak narrative behind his images. He hints at a world that stopped running all at once, people vanished from their homes and villages, making room for a delicate post-apocalyptic world where human construction is all that remains, except for rare shadowy figures seeking warmth in forgotten garages.

There is something Tarkovskian in Prestes’ latest series that he shot in his hometown in Portugal, Guarda. “The Velvet Kingdom” imagines itself as an introspective meditation on solitude and invites us to follow a silhouette wandering through fields and hills in a mystic fog, exploring uncharted territories a la Stalker (1979). Our “Zone” seems to be memories themselves, whether we revisit where we grew up, where we buried a pet, or where we took our lover one afternoon. Prestes reminds us to cherish and care for these memories through a series of photographs that serve as a subtle and benevolent “Memento Mori”.