| #6 | The intersections of Flow and Evil Does Not Exist & Discussions with photographer Chiara Zonca and musician Jason Van Wyk

Plus: A polar bear-driven short documentary

Evil Does Not Exist & Flow — two tales of balance.

Distributors A24 and Neon have been the tentpoles of award seasons for the past years and are a perfect example of healthy rivalry that boosts independent cinema—so, naturally, they are the “plat de resistance” of many conversations. Neon shined with Longlegs, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, and their frontrunner Anora in 2024; while A24 has its protege The Brutalist alongside Queer, the magnificent Sing Sing, or even A Different Man. But another independent American distributor—much older—seems to be the forgotten rhubarb pie left aside from these conversations, possibly because of its smaller scale and more risqué catalog. Janus Films has been a pillar in international independent cinema since they brought us Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal almost 70 years ago, and continues to offer their sizable but niche audiences gems from around the globe. Not for everyone, granted, but films with enough markers to place them in the elusive “important cinema” category—the one that no one can truly define but that everyone recognizes when they see it.

Even though Janus distributed “only” seven movies in 2024, they include high profiles, notably All We Imagine as Light from Indian filmmaker Payal Kapadia and Vermiglio, an Italian drama just hitting theatres. Evil Does Not Exist and Flow are also some of them: one is a live-action Japanese movie with hints of thriller and a deep layer of social commentary; the other is a poetic Latvian animated feature flirting with the fantastic. Quite the range, said like this—but if we juxtapose the two, we realize that they share more DNA than it first seems.

Drive My Car was a huge success, crowned with the Best International Film Oscar in 2021, but Ryusuke Hamaguchi wasn’t sure what to do with his next film which started as a collaborative project with his composer Eiko Ishibashi, who asked him to put images to her music. After a year of not being certain how to even tackle this embryo of a project, he paid a visit to the composer living in a rural village, and only then the seeds of what became Evil Does Not Exist were planted. It is centred around a small rural community relying on traditional lifestyles, including berry picking and using the forest stream as their primary source of water, just the way composer Ishibashi’s community lives. A questionable corporate project aiming to turn the land they live on into a fancy glamping attraction threatens their very ways of life, and they attempt to reason with these people to reconsider their venture—which, as is, plans on draining the tourists’ piss and shit into their drinking water stream.

Just like Hamaguchi, the Latvian director Gints Zilbalodis also found inspiration and answers in nature for his second feature Flow. It is in part during hikes that he came up with his story, studying a cat on an Earth-like planet subject to a sudden and devastating flood that forces the wildlife to embark on a journey, drifting through rough seas and abandoned towns to find “home” but, mostly, themselves.

The two plot lines are intentionally straightforward and minimalist to allow the themes to deploy throughout, especially the large and intricate notion of balance. In Evil Does Not Exist, Hitoshi Omika’s character Takumi warns that the entrepreneurs and the community’s residents need to find balance going forward, because “what happens upstream ends up downstream”, and he’s fully aware of the fragile equilibrium necessary for him and his daughter Hana to continue living in cohesion with their environment. He becomes a little closer with the two employees who were charged with the initial pitch of the project, who make a U-turn on this business idea, touched by the community’s perspective and realizing how ignorant they were. But as much as they want to belong to this sphere and contribute to this balance, they already disrupted it.

Flow’s cat deals with a disrupted balance as well, forced out of its home where it was venerated to embark on a makeshift boat alongside four other animals. Their relationship with their environment is redefined—now more victims of it than inhabitants—and the cat doesn’t hide its vehemence toward the silly dog, the hoarder lemur, or even the laggard capybara, without whom a sense of balance could be found. The cat’s focus is on a majestic bird instead, one that is charismatic and brave, steering the ship like an ace, a mentor and protector, one who is ready to become a pariah of its own community to protect the cat. In what could be described as one of the true cinematic moments of 2024, the bird passes on to another life and the cat is left to fill in for it, becoming the figure that the others rely on and that provides structure and harmony.

When she crosses the woods to get back home from school, young Hana gets wounded by a hunter’s loose bullet. And Takumi warned us: a deer becomes a threat to humans only if gun-wounded, or if their little ones are. So when he finds his daughter’s body, Takumi strangles the corporate employee who was searching the woods with him and leaves his agonizing body in the grass. It’s an instinctive, raw, and primal act—an attempt to silence the agitator once “the deer” realizes the balance has been disrupted. As Takumi carries his daughter home, panting in the forest like an animal on the run, Flow’s cat becomes its most “human” during a similar run when it clocks a stranded whale dying on the grass. A newfound maturity and compassion drive it to bring solace to the dying giant, soon joined by its three companions. After the whale’s final exhale, the animals gaze into a puddle of water, aware of their own reflection, aware of their place within this fragile equilibrium that involves death, aware of the impact they have on each other’s balance.

Where Evil Does Not Exist implies that a disrupted balance has irreversible consequences, Flow points in the other direction, hinting that disruptions in life’s harmony are not only conquerable but a terrain for growth and that we can embrace the cyclical changes of the equilibrium around us. Both Hamaguchi and Zilbalodis conveyed their themes through enigmatic and ambiguous endings, refusing to offer immediate satisfaction and meaning to their audience, preferring to let them sit with it and work to find what they want to extract.

In relation to Kurosawa’s works, Hamaguchi explained his thought process for crafting his ending before detailing why ambiguity is being lost nowadays:

In the ’90s, when he [Kurosawa] was most prolific, a lot of his films had very unclear endings or were left very unresolved, and that unresolved nature is what made those films leave such a deep mark within the viewer. That is something I was really thinking about in making this film and something I was striving towards. […] In the past 20 years, in film, I see that ambiguity is gradually being destroyed. It’s hard to preserve when what’s valued is very momentary or quick responses to art. People are asked to react very quickly, form opinions, or have things to say very fast. In our world, where we live so closely and intertwined with social media, it especially creates a situation where these types of quick reactions are held up, and ambiguity continues to be lost. […] What is ambiguous is what ends up resonating deeply with audiences. This film, and its ambiguity, is one way that I’m resisting the trends of today.

From an interview with Isaac Feldberg on Roger Ebert.

Zilbalodis aimed less for ambiguity and more for nuances, with a mature appraisal of how both insecurities and fear can be forever embedded in us.

I didn’t want the simple happy ending where everything’s solved and the cat learns to overcome everything. I don’t feel like life is like that. There are certain things we can change about ourselves and we can learn and become more brave, but there’s still some anxieties we feel, at least I feel, no matter what. I wanted to show how the cat does improve on its fears, but it still has these deep down, something that it has to learn how to live with. And I wanted to show how that’s okay, and we can accept those things, and maybe there’s others who can support that.

From an interview with Jackson Murphy on Animation Scoop.

In that sense, Zilbalodis’ vision echoes Joshua Rothman’s short essay for The New Yorker about the concept of our deep self in relation to others:

“Does anybody really know you?” might be too narrow, or too rigid, a question, with a passive construction that belies reality. Like Schrödinger’s cat, we may not settle into any particular way of being until someone studies us. Other people help us to know ourselves, working with us to create a shared idea of who we are. So, instead of asking whether we are known, it may be more fruitful to ask whether we’ve arrived, in collaboration with people we care about, at a conception of ourselves that we recognize.

— Joshua Rothman

And when we think about these four animals gazing at their reflection in a puddle next to a dying whale, this is precisely what we are witnessing.

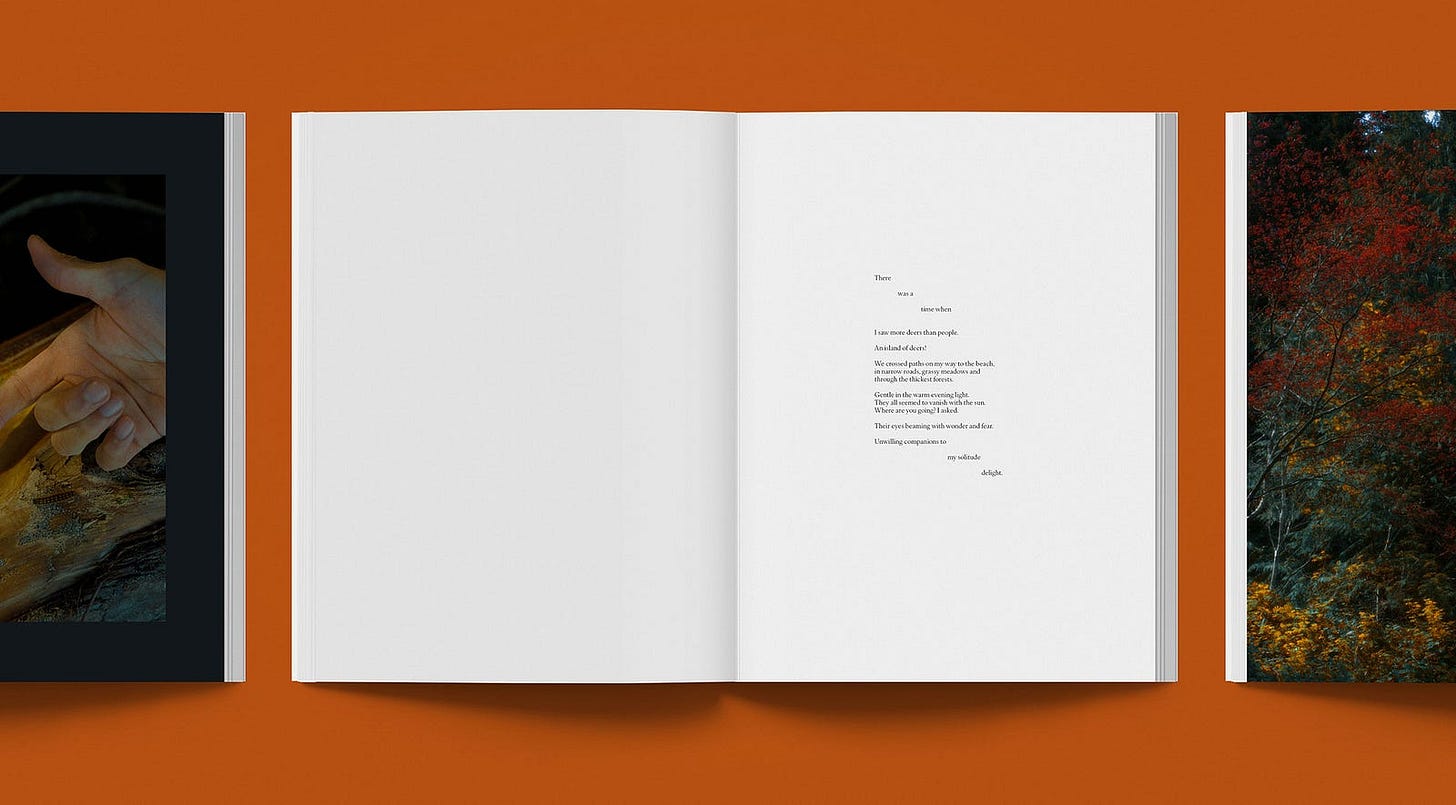

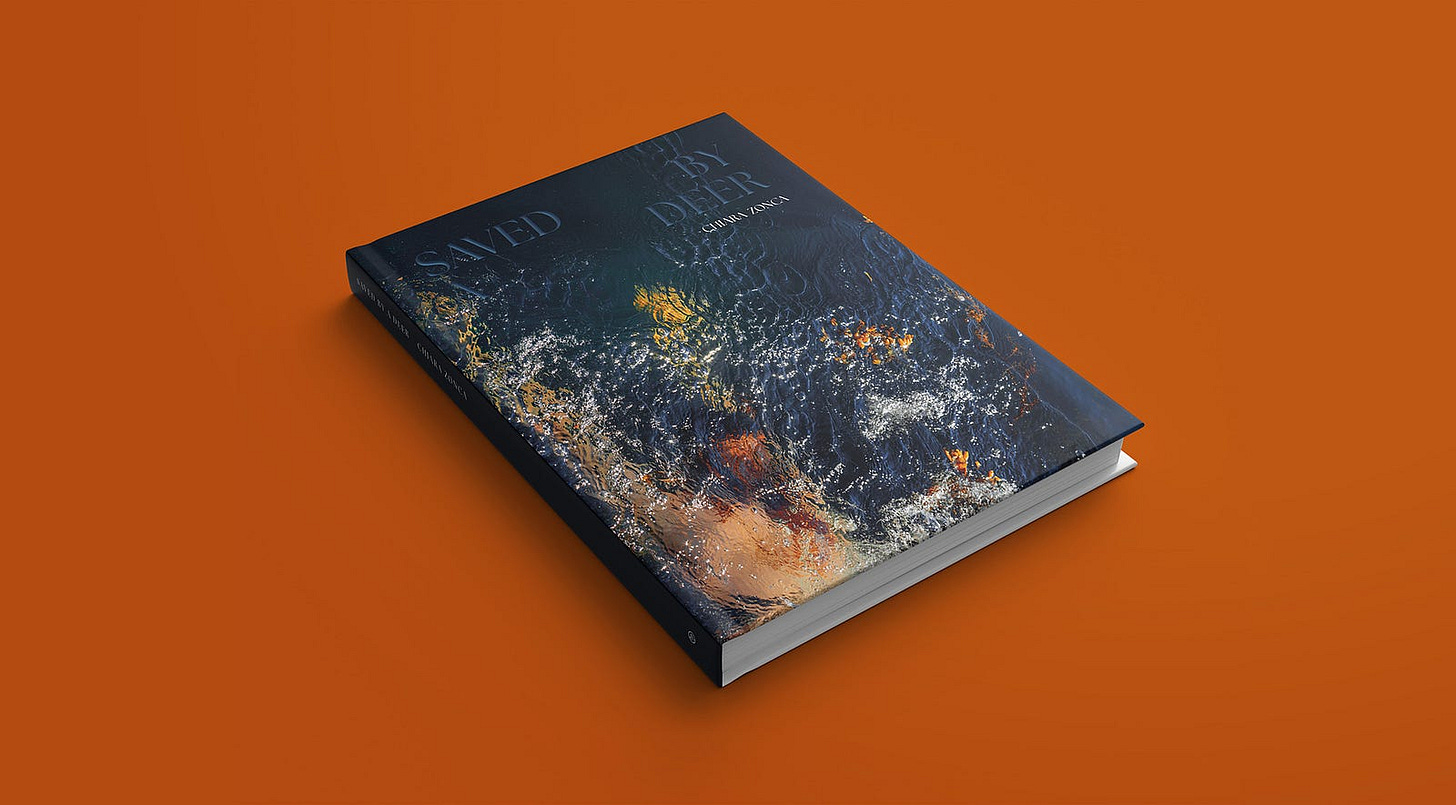

Chiara Zonca’s fleeting moments

It may sound silly but part of my grievances with the world right now is that I don’t fully integrate in society, I never really did. I don’t understand it and worse of all I despise part of it, particularly in the current political climate. Nature is different, when I am in nature I feel like I can truly fit in. There is a weightless, effortless serenity in nature’s presence, a wholesome simplicity of being that temporarily eases my mind of all worries.

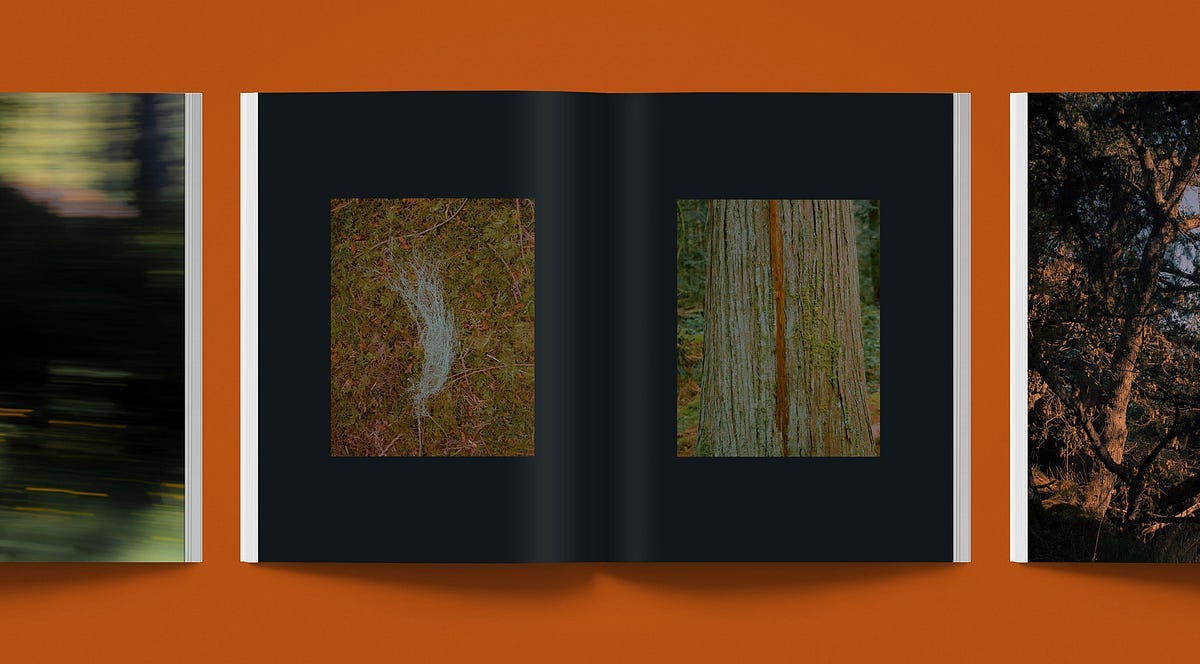

Where Evil Does Not Exist and Flow study the balance within our natural environment, nature is the very element necessary to reach balance for Chiara Zonca, an Italian-born photographer now living in Canada. Dedicated to her craft for about a decade, she captures the ephemeral — these moments and events that come alive for an instant and whose beauty resides in the promise of their disappearance.

Whether it is surreal and minimalist landscapes in her 2019 monograph Desert Portraits or lush nature in between seasons in British Columbia, she features these elusive moments with a unique dream-like tone, helped by a specific color palette—the ripples of the freshwater lake when a body cuts through it, the burgeoning hues of leaves at the turn of a season, a human gaze inhabited by a feeling or idea passing through the mind, imprecise, soon forgotten.

I was able to exchange with Chiara, who, when not working in her studio, meanders on the road in her “home on wheels”. The way she narrates a memory of a meal in the wilderness encapsulates the relationship she has with the open spaces.

I remember a foggy, gloomy morning in Cache creek, British Columbia, a stunning part of the province where desert meets forests. My partner and I were camping in front of the river right by a railway so he could spot the passing trains. I was really aching to be outside but the air was chilly and humid so I decided to start a fire. I particularly enjoy slow cooking over a fire and I decided to make some simple chicken ramen soup. Taking my time to prepare it and savour it along with some ginger tea was an absolute delight. I vividly remember us sitting in front of the campfire, looking at the slow moving river below and just enjoying a warm and hearty meal. The simplicity of this lifestyle is what drew me in and keeps me going.

All the pictures featured here and taken from her upcoming monograph, Saved by a Deer, where poems act as companion pieces to her visuals. She considers her approach to photography and poetry identical, in the sense that she aims to capture a fleeting feeling or emotion in a deeply subjective manner, reflecting her perception of the outside world.

In a similar fashion, I love the type of poetry that describes subjects in surprising, thought-provoking ways. Much like a certain smell can be linked to a memory or a place forever, words, when done right, have a weight to them you can’t shake off. I love that about poetry.

Photography and poetry were two mediums that, when dovetailed together, properly honored the island she’s been living on in British Columbia—but the first seed of the book started before, when she was stranded in the cold prairies by the pandemic.

Like many others, I lost most of my work opportunities in a matter of weeks and found myself in a really bad place. I was living in Saskatoon at the time, a city I suddenly couldn’t leave, with no nature, friends and with way too much time on my hands to let my mind sway into dark corners. Moments of intense pain where followed by days where I just sat in bed feeling numb and not being able to move or do anything at all.

After six difficult months, she and her partner had an impulse to relocate to the West, where they had traveled before and spent some time in the Southern Gulf island of British Columbia.

I had a sense that move would at least get me closer to nature, to sanity. And I was right. From the silent walks in nature, the meals cooked on the patio glancing at the dark starry skies, the incredible scent of the ground — an intoxicating mix of wet grass, ocean spray and pine trees- the island started to work its magic on me and I slowly felt happier to be alive and outside.

She started documenting this transition in photographic excursions in her newfound natural environment, closer to journal entries than a clear monograph project at the time. The aim was merely to convey the little joys she found in her surroundings and to check in on herself, day after day.

Interestingly I was suddenly getting more open to discuss my issues with depression, to accept it and try to live with it. Four years, a few housing changes and an island swap later, this project is now becoming a book and is far from over. I am still interested in creating new material on the topic of island living and mental health. I suppose I’ll be doing it for as long as I live there.

Her island was the vehicle through which her approach to balance and mental health morphed and crystalized, a delicate ongoing journey that she documents with a lot of poetry in her book, but her nomadic instinct remains present—and essential to her craft. She thrives in constant change, her creativity thrusting when she’s on the move.

For the longest time I thought this nomadic impulse was just deep curiosity, sense of freedom and genuine love for travel. Now that I am much more aware of what goes on in my head I know there’s a darker side to it. I am always running from something, running away from pain I guess. If I stay anywhere long enough I might be faced with feelings I can’t fully control.

And she embraces parts of this darkness, recognizing its potential value and the fact that, to conquer the dark, we must first understand it.

After that realization hit I started to embrace a slower approach, making sure I get to spend enough time in one place to fully absorb it. Taking everything in, inner darkness, turmoil and creative bliss. This feels like a better path towards inner growth.

Her upcoming book Saved by a Deer can be pre-ordered here. Chiara Zonca can be found on her website and on her Instagram account, but also on Substack.

Jason Van Wyk’s pensive music

At the end of our conversation, I asked Chiara Zonca to describe what she pictures when she listens to Cape Town-based composer Jason Van Wyk’s music.

I think he captured the sound of mountain air, like slow-moving clouds across snow-capped peaks. And a beautiful starry sky.

There is an overlap between Van Wyk’s music and a mountain, both imposing and fragile, offering textures ranging from soft larch tree needles at its base all the way up to cold and sharp moraine and crevasses in the glacier. The feelings of quietude and awe we can find contemplating a peak are especially present in the composer's first three records, Days You Remember (2013), Attachment (2016), and Opacity (2017), featuring serene strata of ambient and drone that only a gentle piano disrupts, like a squall piercing through the fog. His most recent works, Threads (2021) and Descendants (2022), seem to focus more on the moraine and the crevasses—the textures are more abrasive, the landscapes more hostile, and a sense of scope imposes itself and creates vertigo.

I exchanged extensively with Jason and he detailed the difference in approach between these records.

Opacity was made as the follow up to my second album Attachment. Both of them share a similar sound as they were put together from the same recording sessions. Threads was a conscious departure from that. Besides the difference in mood, less piano was used, a lot more electronics were involved and all the acoustic stuff was heavily processed. The album also took a lot longer to make and was more experimental in its production. The only real guideline I gave myself with Threads was that I wanted to focus more on texture and to try and blur the lines more between the electronic and acoustic sounds used.

The album he mentions, Threads, was his first work on his current label n5MD, a reference in the ambient music sphere. As Jason described, the piano is more discreet and cohabits with textures that rise and fall, evoking a different form of beauty and quietude—maybe of a more mature kind, less obvious and immediate, asking more of its listener to be found. One track in particular functions this way, Subdued, the shortest one of the album—a simple but hypnotic piano phrase accompanies us during the first half of the track before leaving us with impactful drones, and ultimately what sounds like strings.

Subdued came about through some cello improvisations. I can’t play cello at all, but I ended up with one in my studio for a few weeks, looking after it for a family member. After some YouTube tutorials, I recorded myself messing about with it. Layering those recordings and running them through various effects resulted in the ending section of that track. The rest of it branched out from there. Besides the piano, most of the sounds on Subdued are derived from those cello recordings being manipulated.

His latest album Descendants continued this trend, preferring the complexity of textured drones to the comfort of the piano. Besides his five records, Jason was also commissioned to work on audiovisual works, including on a Criterion Collection’s short documentary about the artist Richard Haine, the feature film Triggered (2019), or, very recently, the Nikon Short Film Tu connais l’amour (2025). These collaborations impacted his creative process but also forced him to thrive within the constraints he was given.

Becoming more involved with music for film and visual media was definitely a turning point. It pushed me further in the way I produce music as well as the way I listen to and think about sound. […] It’s not always the case, but restrictions can sometimes be a very good thing. Having a strict deadline for instance forces me to not second guess what I’m doing. I commit to the first idea and move on, which definitely frees up creativity in a way, opposed to how I make an album which is very open ended. Both situations have their merits.

As for adapting to it, I love the process of writing music to picture and I treat it the same as any sort of collaboration. As long as I’m working with collaborative, open minded and creative people, I’m happy.

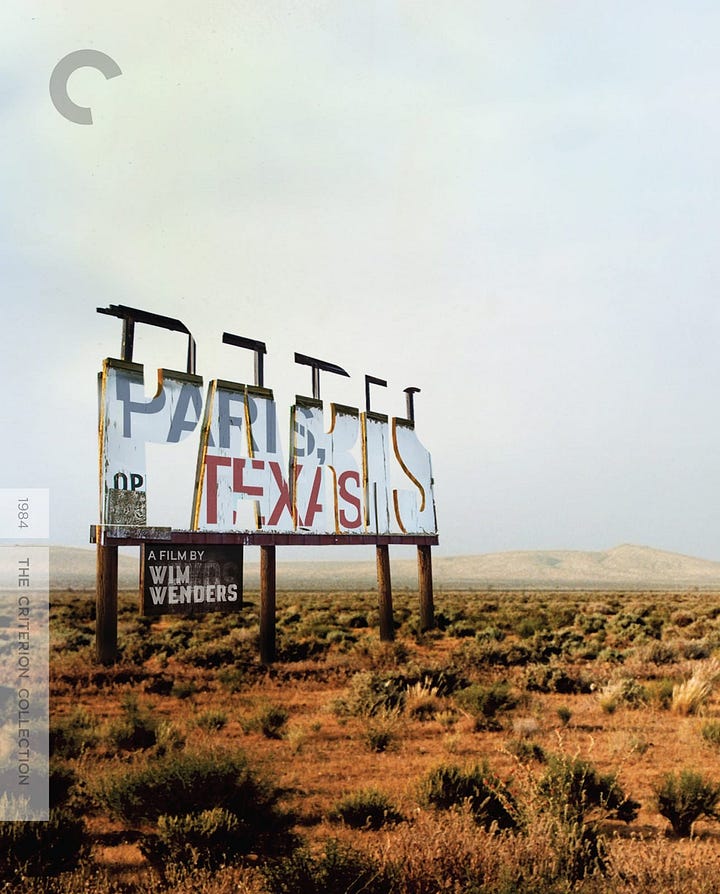

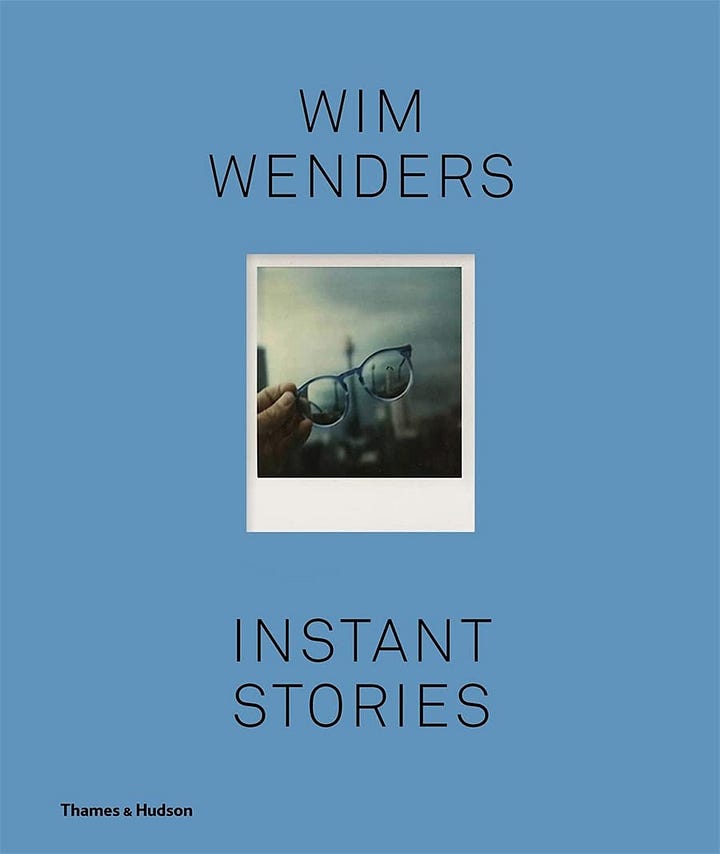

Speaking of composing for the screen, Jason shares a movie and an artist he’s recently been deeply inspired by, Wim Wenders.

I’ve been on a bit of a Wim Wenders binge lately. Paris Texas has always been a firm favourite of mine, but a lot of his other films I hadn’t seen or it’s been many many years since I last did. His book “Instant Stories” has also been on my bedside table for the past few weeks which is really excellent.

Two atmosphere-heavy pieces that are not surprising for the South African composer, for who mood and atmosphere are pillars in his process.

Mood and atmosphere are always the driving forces for me. […] Emotions can dictate the atmosphere and vice versa. The production, the instruments, the notes used, to me that’s all secondary to how a piece of music sets a mood and makes the listener feel. It’s what I’ve always been drawn to in music, whether I’m listening to it or making it.

Jason is putting the final touches on a new album that will come out in 2025, following the steps of Threads and Descendants. You can follow him on his website, Bandcamp, and Instagram.

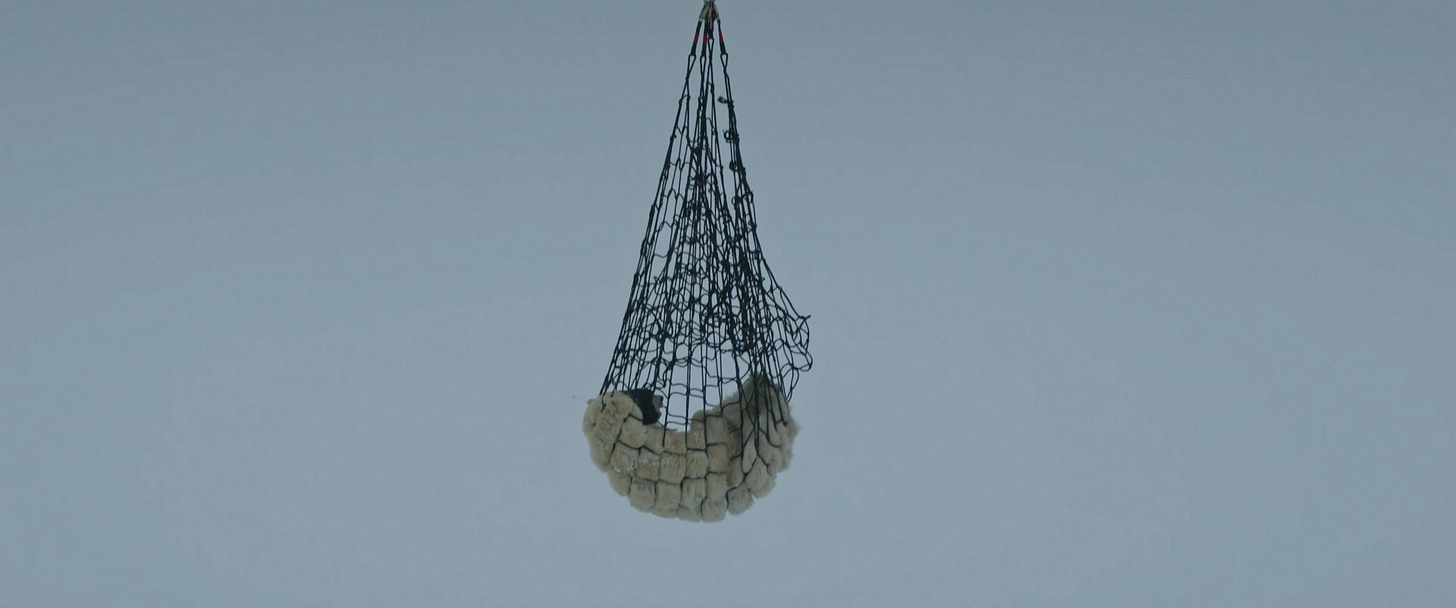

Nuisance Bear—On an uncanny cohabitation

If you were to ask someone where their insecurities lie when they walk home from work, at night and on their own, and they would simply answer “polar bears”, you’d probably think they’re fucking with you. Either that, or they’re from Churchill, Manitoba — one of the northernmost communities of the Canadian province nicknamed “the polar bear capital of the world”.

In October and November, polar bears are particularly present in the area, where they temporarily abandon their solitary nature to mate before the water freezes on the Hudson Bay, signalling the start of their seal hunting season. Even though the vast majority stay on the peninsula, some make their way into the small town itself, where they roam in the streets, guided by their nose up in the air to the nearest trash can. Their presence in town changed inhabitants’ behaviors, most of them leaving their cars unlocked in case someone needs to quickly find shelter if facing one of these puppies, and there is even a Polar Bear Holding Facility where the “intruders and loiters” are held until they can be safely brought on the ice.

Jack Weisman and Gabriela Osio Vanden’s documentary for The New Yorker is a testimony of this uncanny cohabitation, told from the bear’s perspective. No narrator, no annoying news anchor, and no one to feed us facts. We roam alongside the animal, explore with it these metallic and caged areas from where the smell of leftover pizza comes from, and eventually run away as the authorities chase it. Choosing this perspective and making the bold choice of censuring themselves from voice-over present this cohabitation in its most naked and immersive fashion, forcing us to piece everything together on our own, as if we were the ones sheltered behind a car, the white giant giving us the once over from the other side of the road.

The filmmakers don’t structure their work as a lecture on wildlife and human cohabitation or the impact of climate change on these interactions, and instead present us the raw reality of life in this Sub-arctic region, where polar bears, stubborn to survive before they can meander on the ice, enter what seems to be “our space”. This question of sharing habitats is raised in the viewer’s mind once the credits roll, leaving them to ponder, not necessarily “What would I do if I ended up face to face with a polar bear?” but more “What would I do if I were one?”

Previous collection —

a beautiful collection! every time i read your stuff i put new things on my music playlist and on a list of things i must dig deeper into. much love!

definitely checking out Chiara Zonca’s work!! gorgeous photos!!